Weeksville Heritage Center

We’re committed to uplifting Brooklyn’s Black-owned businesses, but we’re also about our local institutions. As we approach the midpoint of Black Business Month, today we reflect on the entrepreneurs who came before us with a visit to the Weeksville Heritage Center, a historic site in what is now Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Founded in 1838, Weeksville was a free African-American community, the second largest, in the pre-Civil War era. The settlement was named for James Weeks, a stevedore who was born into slavery and gained his freedom, acquiring property, along with other African-American investors, to build a self-sufficient town. We learned more about Weeksville from the center’s tour educator Zenzelé Cooper.

The free African-American community of Weeksville, Brooklyn was founded in 1838, 11 years after slavery was officially abolished in New York in 1827, and almost three decades before it was abolished nationally in 1865 with the end of the Civil War.

“They were living in a society where they’re free in the midst of slavery,” said Cooper. “You could be kidnapped and forced back into slavery, so it was a very delicate experience. There was racial violence, riots and bigotry. It was this major contradiction: Can you really be free in the midst of slavery?”

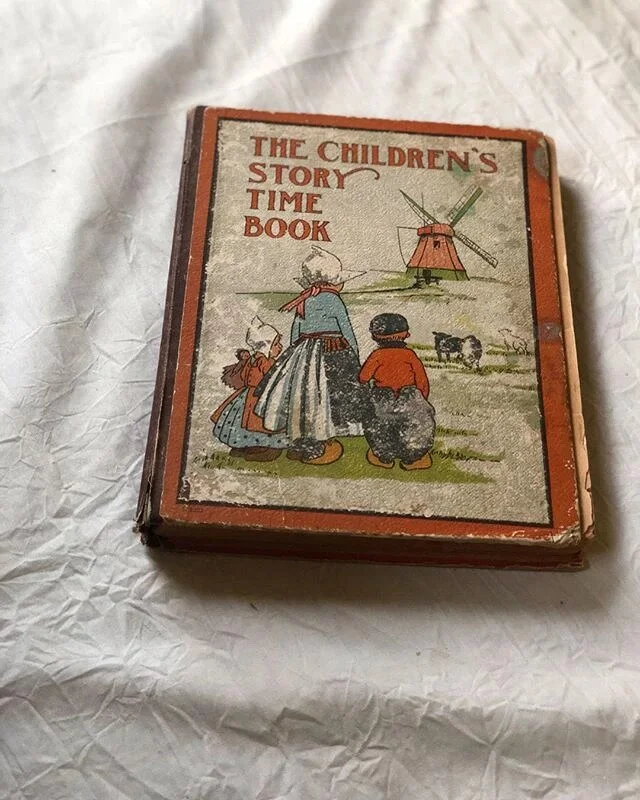

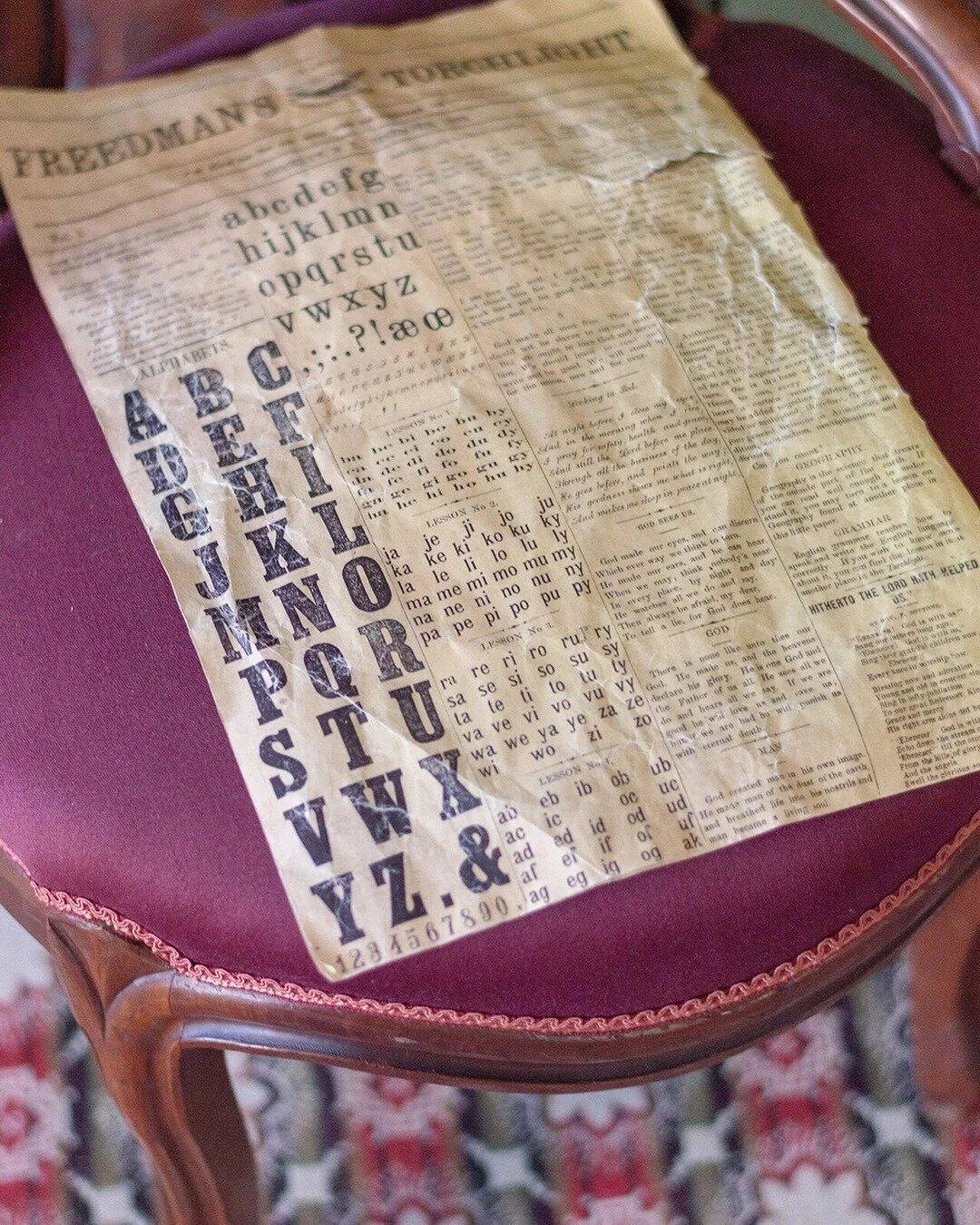

By the 1850s, the remote farming village was home to about 525 families who lived in wooden-framed houses, three of which are still intact. Residents enjoyed a self-sufficient life with teachers, doctors, carpenters, barbers, bootmakers, seamstresses, butchers, bakers and other occupations. The town developed important community institutions, including its own schools, hospital, orphanage, retirement home, churches and a newspaper, The Freedman’s Torchlight.

“Out of all the free Black communities that existed prior to the Civil War, Weeksville had the highest land ownership and the most occupational diversity,” said Cooper. “Everything you really needed was right within your own community.”

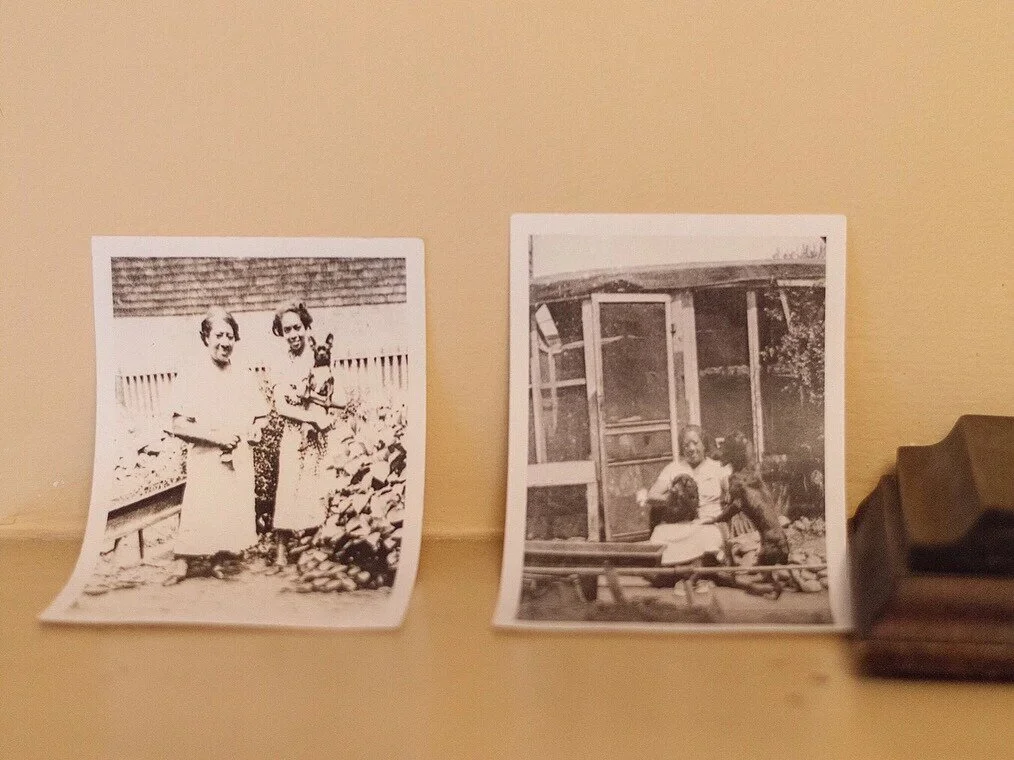

Weeksville’s three remaining houses, containing mid-19th century furniture and other artifacts, sit on what was once called Hunterfly Road. Although the community existed until the 1930s, it was overtaken by urban renewal plans.

“In 1940, they started building Kingsborough housing [projects] and started demolishing these old wooden structures,” says Cooper. “Weeksville was absorbed into Bedford-Stuyvesant, so if you moved to the community after the 1940s, you didn’t know it as Weeksville because nobody called it that.”

But she refrains from saying that the town was forgotten. “Weeksville was an oral history — people talked about it and knew about it,” she said. “But it takes years of research and scholarship to go from telling a story to putting it down on paper and getting it out there.”

Some of this intellectual labor was taken up by Pratt Institute historian Jim Hurley, who re-discovered what was left of historic Weeksville in 1968. After a fruitful archeological dig of the area, conducted by Hurley’s students and youth in the community, the Hunterfly Road houses were declared New York City landmarks, with the site ultimately becoming the Weeksville Heritage Center.

“Out of all the free Black communities that existed prior to the Civil War, Weeksville had the highest land ownership and the most occupational diversity. Everything you really needed was right within your own community.”

The emergence of the Weeksville Heritage Center, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, was part of a larger Black Museum Movement of the 1960s and 70s.

“All around the country, we were creating museums that elevated and gave reverence to the communities we were in,” said Cooper. “Weeksville’s museum wanted to reassert the stories of the people who lived here, the objects that they used, and the institutions that they created to highlight their particular way of life.”

Fifty years later, the Weeksville Heritage Center continues this tradition from an expanded visitor’s center that also hosts performances, educational programming and outdoor concerts in its large meadow garden.

“Weeksville is a little-known history, and we want it to be a well-known history,” said Cooper. “We try to take the values from Weeksville — the entrepreneurship and creativity that existed, and the self-sufficiency that the people had — and use them as a blueprint. History is a living memory. Those same values that helped build this thriving community 180 years ago are the same things that we can use today.”

158 Buffalo Avenue, 718-756-5250, weeksvillesociety.org